John K. Strickland

Elon Musk’s SpaceX has enormous implications for Mars. When Musk’s reusable rockets and upcoming reusable spacecraft become a reality, Mars missions will be possible at one-tenth the cost of the Mars plan NASA now has on its books. One such low-cost Mars plan comes from the Space Development Steering Committee’s chief analyst John Strickland. Working with artist Anna Nesterova, Strickland has developed the following program.

SpaceX’s Falcon-based reusable boosters will carry vehicles and crew that will travel to Mars. A Falcon-based super-booster can carry 220 tons.

A logistics base will remain in low Earth orbit. At this base, the cargos launched from Earth are attached to in-space propulsion units, units that will carry them to another logistics base further out in space. The next destination will be a space truck stop at a gravitational “balance point” between the earth and the Moon called L1. L1 provides an advantage—with minimal fuel you can stay in place. And there’s a bonus at L1–no space debris.

The L1 logistics base will be built by robots. First they will build a long, docking truss. Why is it called a “docking truss”? Because this truss will provide docking, unloading, loading, and refueling facilities for cargos and vehicles doing the transport runs between the Earth, the Moon, and Mars. This logistics base will be a full-service space truck stop and cargo depot.

The L1 truck stop will also be used for trips to the Moon and back. Those trips can be very fruitful. The moon’s water can be used to make the rocket fuel with which the truck stop refuels all the vehicles based at it. This Includes a fleet of vehicles headed for Mars.

At the L1 docking truss, key elements of the first Mars mission will be assembled in space. This Mars fleet will consist of twenty two vehicles. There will be twelve large vehicles designed to stay in Mars orbit, and each will have a 100 foot wide aero-capture heat shield. The heat shield will use the Martian atmosphere as an air brake to ease the vehicle into orbit without using up valuable fuel. Meanwhile, there will be ten Mars ferries that will go back and forth from Mars orbit to the red planet’s surface. Seven ferries will carry cargo, and three will carry crew.

The Mars-bound crew clusters will go into low Mars orbit and stay there. Two will support the crew operations before and during a landing, but they will not land.

Two crew clusters are docked together, a fact that has allowed the crews to work together during the long voyage to Mars. Within a few hours, the crew clusters will separate and reconfigure. They will deploy two extra heat shields. Why? To protect the propulsion modules that have thrust them into an Earth-Mars transit orbit. Each propulsion module will use an aerocapture shield as an air brake to slow itself without using up fuel. It will park in Mars orbit, where it will wait to provide propulsion for the trip back to Earth.

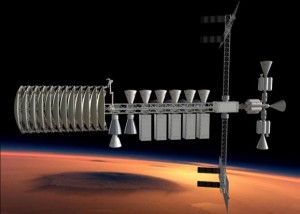

Above, the Mars fleet has arrived safely in Low Mars Orbit. A robot on rails has built a Low Mars Orbit logistics base, and all the fleet’s vehicles have docked at the base. The robot has stacked all of the aero-shields like pancakes out of the way at the left end of the truss. The vehicles that the shields protected during aero-capture are not designed to land. They are crew clusters, propulsion modules, propellant depots and large cargo carriers. Mars landings are handled entirely by the ten conical Mars ferries. Three of these ferries carry crew. In this picture, one of the seven cargo ferries is taking on fuel from a depot before landing on Mars. Together, the ten ferries can land over 600 metric tons of crew, habitats, food, equipment and rovers on Mars by making multiple trips. Art: Anna Nesterova

In the final picture above, the seven cargo ferries have landed the equipment (far right) to produce at least 100 tons of fuel per month from Mars ice and to set up a habitat for the crew. Now, that the first 100 tons of propellant have been produced and stored, one ferry has enough fuel to go back into orbit. In this picture the first crew ferry (in the foreground) has safely landed with even more cargo for the Mars base and with humans. The ferries descend and take off at a landing zone well away from the base itself for safety. The cargo container is pulled directly out of the Ferry’s cargo bay with a winch.

John Strickland’s Mars mission is not a quickie. It is not a flags and footprints mission. It builds a permanent transport infrastructure in space. And once we start landing this program’s components on Mars, we are on Mars to stay.

Art: Marcus Mashburn